The events of July 14, 1789, in Paris were the culmination of a confluence of socio-political and economic pressures that had been building for years. Years of fiscal mismanagement by the French monarchy, exacerbated by involvement in costly wars such as the American Revolution, had left the nation teetering on the brink of bankruptcy. This financial instability led to increased taxes, particularly burdening the Third Estate the commoners and bourgeoisie while the privileged First and Second Estates (clergy and nobility) largely evaded taxation. A severe economic downturn in the late 1780s, characterized by poor harvests and rising bread prices, further fueled widespread discontent and desperation among the populace.

The significance of these antecedent conditions lies in their contribution to a pervasive sense of injustice and inequality. The perceived indifference of the ruling class to the suffering of the general population fostered resentment and a growing desire for systemic change. Enlightenment ideals, advocating for liberty, equality, and popular sovereignty, provided an intellectual framework and justification for challenging the established order. The Estates-General, convened in May 1789 to address the financial crisis, became a battleground for these competing interests, ultimately leading to the formation of the National Assembly and the Tennis Court Oath defiant acts that signaled a breakdown in royal authority.

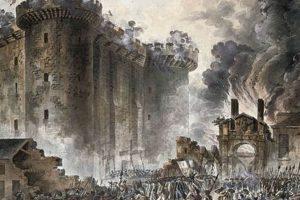

Against this backdrop of economic hardship, political tension, and ideological ferment, the dismissal of Jacques Necker, a popular minister perceived as sympathetic to the Third Estate, acted as a catalyst. Rumors of royal troops massing in Paris further inflamed anxieties, leading Parisians to seek arms and defend themselves against perceived royalist aggression. The search for gunpowder and weapons culminated in a pivotal event: the targeting of a medieval fortress used as a prison. This action, motivated by a combination of desperation, revolutionary zeal, and the desire to secure resources for self-defense, marked a turning point in the French Revolution.

Understanding the Precursors to a Revolutionary Event

Analyzing the environment preceding a historical occurrence necessitates a meticulous examination of interwoven factors. Concentrating solely on the singular event overlooks the complex web of circumstances that coalesced to produce the outcome.

Tip 1: Recognize Economic Instability: Governmental fiscal irresponsibility, coupled with unequal distribution of wealth, invariably breeds widespread discontent. Study the financial policies and tax structures of the era. For instance, the heavy taxation disproportionately impacting the Third Estate in pre-revolutionary France played a crucial role.

Tip 2: Acknowledge Social Inequality: Investigate the stratification of society and the inherent privileges enjoyed by certain segments. The vast disparity between the nobility and the commoners concerning rights and obligations was a key contributor to the burgeoning revolutionary sentiment.

Tip 3: Evaluate the Impact of Ideas: Examine the role of intellectual movements in shaping public opinion. Enlightenment philosophies, emphasizing reason, individual rights, and self-governance, offered a compelling challenge to the existing political order.

Tip 4: Identify Political Tensions: Scrutinize the power dynamics between the ruling authority and the populace. The monarchy’s perceived inflexibility and resistance to reform intensified the conflict and fostered a climate of opposition.

Tip 5: Analyze Immediate Catalysts: Identify the specific triggers that transformed underlying tensions into open rebellion. The dismissal of popular figures and the mobilization of troops often served as sparks, igniting the pre-existing resentment.

Tip 6: Consider the Role of Information: Assess how information (or misinformation) spread and influenced public perception. Rumors, pamphlets, and public discourse played a significant role in shaping the narrative and mobilizing support for the cause. The perception, true or not, that royal forces were poised to suppress dissent was a major factor.

Tip 7: Understand the Element of Fear: Recognize how fear of retribution, starvation, or governmental overreach can motivate drastic action. The populace, already burdened by economic hardship, was susceptible to anxieties that amplified their revolutionary fervor.

A comprehensive understanding demands a holistic perspective, acknowledging the interplay of economic, social, intellectual, and political forces. This approach facilitates a more accurate and nuanced assessment of historical causation.

By considering these various layers, a fuller understanding of the series of events that dramatically altered the course of history becomes achievable.

1. Fiscal Crisis

The French monarchy’s persistent fiscal crisis served as a fundamental catalyst leading to the events of July 14, 1789. Decades of extravagant spending by the royal court, coupled with involvement in numerous costly wars, most notably the American Revolution, had depleted the national treasury. This financial strain was exacerbated by an antiquated and inequitable tax system. The nobility and clergy, comprising the First and Second Estates, enjoyed significant exemptions from taxation, placing the burden disproportionately on the Third Estate, which included commoners, peasants, and the burgeoning bourgeoisie. This inequitable system ensured that those least able to afford it bore the brunt of the government’s financial woes.

The consequences of this fiscal mismanagement were far-reaching. As the government struggled to meet its financial obligations, it resorted to increasing taxes and devaluing currency, further eroding the economic stability of the Third Estate. Poor harvests in the years preceding 1789 led to soaring bread prices, the staple food for the majority of the population. Faced with both rising taxes and the increased cost of basic necessities, many families were pushed to the brink of starvation. The perception that the monarchy was indifferent to the suffering of its people, while continuing to live in opulence, fueled widespread resentment and a growing sense of injustice. For instance, the construction and maintenance of the Palace of Versailles, a symbol of royal extravagance, became a lightning rod for criticism during times of economic hardship for the French population.

In summary, the fiscal crisis was not merely an economic issue; it was a critical component in the build-up to revolution. It created a climate of economic hardship, social inequality, and political instability, making the Third Estate more receptive to revolutionary ideas and more willing to take direct action against the perceived source of their suffering. The economic hardship played a pivotal role in making the event of the Bastille a viable tipping point for wider revolution.

2. Social Inequality

Social inequality within pre-revolutionary France constituted a significant factor contributing directly to the conditions that precipitated the events of July 14, 1789. The rigid hierarchical structure of French society, characterized by vast disparities in privilege and opportunity, fostered widespread resentment and discontent, providing fertile ground for revolutionary sentiment.

- The Three Estates System

French society was divided into three distinct orders, known as Estates: the clergy (First Estate), the nobility (Second Estate), and the commoners (Third Estate). The First and Second Estates, representing a small minority of the population, enjoyed extensive privileges, including exemption from most taxes, access to high offices, and ownership of significant amounts of land. The Third Estate, comprising the vast majority of the population, bore the burden of taxation and lacked meaningful political representation. This inherently unequal system created a deep sense of injustice and resentment among the Third Estate, who felt marginalized and oppressed.

- Economic Disparities

The economic inequalities mirrored the social hierarchy. While the nobility and clergy possessed considerable wealth, derived from land ownership and feudal dues, the majority of the Third Estate struggled to survive. Peasants faced heavy taxes and feudal obligations, leaving them with little to no surplus. Urban workers and artisans faced low wages and precarious employment. The burgeoning bourgeoisie, while relatively prosperous, resented their exclusion from political power and the privileges enjoyed by the aristocracy. These economic disparities fueled social tensions and contributed to a growing sense of grievance within the Third Estate.

- Lack of Political Representation

The Third Estate’s lack of effective political representation further exacerbated the sense of inequality. The Estates-General, a representative assembly of the three Estates, had not been convened for over 175 years. When it was finally called in 1789, the voting structure favored the First and Second Estates, effectively silencing the voice of the Third Estate. This political marginalization fueled demands for greater representation and political reform, ultimately leading to the formation of the National Assembly and the Tennis Court Oath, acts of defiance that challenged the authority of the monarchy.

- Feudal Obligations

The persistence of feudal obligations imposed upon peasants represented another significant source of social inequality. These obligations, remnants of the medieval feudal system, required peasants to provide labor services and pay dues to their landlords, further burdening their already precarious economic situation. The resentment generated by these obligations contributed to a widespread desire for the abolition of feudalism and the establishment of a more equitable social order.

The pervasive social inequality within pre-revolutionary France, characterized by the rigid Estates system, economic disparities, political marginalization, and feudal obligations, created a volatile social climate ripe for revolution. This injustice contributed to the widespread desire for change.

3. Enlightenment Ideals

Enlightenment Ideals profoundly shaped the intellectual and political landscape preceding the events of July 14, 1789. Philosophers such as John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and Montesquieu articulated principles that directly challenged the legitimacy of absolute monarchy and the aristocratic privileges prevalent in France. Locke’s concept of natural rights, emphasizing inherent individual freedoms to life, liberty, and property, provided a philosophical justification for challenging the authority of a government that infringed upon those rights. Rousseau’s theory of the social contract, positing that government derives its legitimacy from the consent of the governed, further undermined the divine right of kings and promoted the idea of popular sovereignty. Montesquieu’s advocacy for the separation of powers, designed to prevent tyranny by dividing governmental authority among different branches, offered a model for a more balanced and representative system of governance. These ideas, disseminated through books, pamphlets, and salons, resonated with the educated members of the Third Estate, including the bourgeoisie, who increasingly questioned the established order.

The practical impact of Enlightenment thought can be observed in the growing demand for political reform and social justice within French society. The bourgeoisie, inspired by Enlightenment ideals, sought greater political representation and an end to the privileges enjoyed by the nobility and clergy. They championed the concept of equality before the law and advocated for a meritocratic system that would allow individuals to rise based on their talent and abilities, rather than their birthright. Furthermore, Enlightenment ideals contributed to a growing awareness of the injustices of the feudal system and the economic hardships faced by the peasantry. The emphasis on reason and critical thinking encouraged individuals to question traditional beliefs and customs, fostering a climate of intellectual ferment and challenging the authority of the Church and the aristocracy. For example, the formation of the National Assembly and the Tennis Court Oath were direct manifestations of Enlightenment principles, reflecting the determination of the Third Estate to assert its rights and establish a more just and equitable political system. Enlightenment values directly influenced the drafting of “The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen”.

In summary, Enlightenment Ideals were a critical catalyst in the events leading to the storming of the Bastille. By providing a philosophical framework for challenging the legitimacy of the established order, promoting the principles of individual rights and popular sovereignty, and fostering a climate of intellectual ferment, Enlightenment thought fueled the growing demand for political reform and social justice within French society. The ideas espoused by Enlightenment philosophers provided the intellectual ammunition for the Third Estate to challenge the authority of the monarchy and the aristocracy, ultimately contributing to the outbreak of the French Revolution.

4. Political Impasse

The political impasse between the French monarchy and various segments of French society, particularly the Third Estate and elements of the nobility advocating reform, formed a crucial precondition for the events of July 14, 1789. This deadlock, characterized by a persistent inability to achieve meaningful consensus or compromise on critical issues facing the nation, amplified existing tensions and ultimately contributed to the escalation of unrest that culminated in the action against the Bastille. The monarchy’s resistance to significant reform efforts, particularly concerning taxation and representation, created a sense of frustration and hopelessness among those seeking change. This inability to enact systemic change created a cycle of increasing frustration and anger that spurred some to direct and revolutionary action. The Estates-General, intended to address Frances growing crisis, rapidly became an arena for intractable conflict as the Third Estate’s demands for equal representation and voting by head were rejected by the privileged orders and the king. This rejection underscored the monarchy’s unwillingness to yield power or address the fundamental inequalities that plagued French society.

The formation of the National Assembly, a direct challenge to royal authority, exemplified the breakdown of traditional political structures and the emergence of a parallel governing body. The Tennis Court Oath, in which members of the Assembly pledged not to disband until a constitution was established, further demonstrated the determination of the Third Estate to assert its will and overcome the political obstructionism of the monarchy. Attempts by the king to suppress the National Assembly, including the deployment of troops around Paris, only served to intensify public anxiety and solidify support for the Assembly’s cause. The dismissal of Jacques Necker, a popular minister perceived as sympathetic to the Third Estate, was widely interpreted as a sign of the monarchy’s intention to crush any attempt at reform, thereby providing the immediate spark that ignited popular unrest. The perceived threat of royal repression, combined with the absence of a legitimate avenue for addressing grievances, motivated Parisians to take direct action, seizing arms and ultimately storming the Bastille in search of gunpowder and weapons.

In essence, the political impasse served as a breeding ground for radicalization and violence. The monarchy’s intransigence and failure to engage in meaningful dialogue with those seeking reform left the populace with a sense that extra-legal measures were the only means of achieving their goals. The Bastille, as a symbol of royal authority and arbitrary imprisonment, became a target for this pent-up frustration and resentment. Understanding this political deadlock and it’s effect on revolutionary fever is paramount to understanding the events and reasoning behind the assault on the fortress.

5. Popular Unrest

Popular unrest in pre-revolutionary France was a multifaceted phenomenon directly linked to the events that transpired at the Bastille. It was not a spontaneous outburst, but the culmination of prolonged economic hardship, social injustice, and perceived political oppression, all contributing to an atmosphere of widespread discontent. The populace, primarily the Third Estate, endured a confluence of challenges: escalating bread prices due to poor harvests, heavy taxation that disproportionately burdened them while the privileged classes remained largely exempt, and limited access to political representation. This created a volatile environment in which any perceived slight or act of aggression by the monarchy could trigger immediate and forceful reactions. The dismissal of Jacques Necker, a figure viewed as sympathetic to the plight of the common people, served as such a trigger, catalyzing the latent anger into overt action. The perception that royal troops were being mobilized to suppress dissent further heightened anxieties and fears, leading many Parisians to believe that their only recourse was to arm themselves and defend against perceived royalist aggression.

The Bastille, a medieval fortress used as a prison, became a symbolic target for this burgeoning unrest. Although by 1789 it housed relatively few prisoners, it represented the arbitrary authority of the monarchy and the system of lettres de cachet, royal warrants that allowed for imprisonment without due process. The search for gunpowder and weapons to defend against potential royalist attacks was the immediate motivation for approaching the Bastille, but the underlying impetus was a deep-seated resentment towards the perceived injustices of the ancien rgime. The storming of the Bastille was not simply an act of violence; it was a symbolic assault on the structures of power that had long oppressed the common people. This act of defiance resonated throughout Paris and beyond, galvanizing support for the revolution and signaling a decisive shift in the balance of power.

Understanding the connection between popular unrest and the events at the Bastille is essential for comprehending the broader dynamics of the French Revolution. It highlights the crucial role that public sentiment and collective action can play in challenging established authority. It also underscores the importance of addressing the underlying causes of social and economic inequality to prevent the eruption of violent conflict. Analyzing popular unrest and its influence provides insight for modern-day analysts and political scientists observing similar conditions and movements. The study of revolutionary movements also allows the construction of preventative structures within societies across the globe. The long-term significance of the Bastille is the lessons of revolution and the impact of the people.

Frequently Asked Questions Regarding the Antecedents to the Bastille Event

This section addresses common inquiries concerning the complex factors contributing to the events surrounding the Bastille in 1789. The information presented seeks to provide clarity and informed understanding of the historical context.

Question 1: Was the assault on the Bastille primarily motivated by the desire to liberate political prisoners?

While the Bastille did house prisoners, the number at the time of the assault was relatively small. The primary motivation was the acquisition of gunpowder and weapons to defend against perceived royalist aggression, coupled with the symbolic significance of the Bastille as a representation of royal authority and arbitrary imprisonment.

Question 2: To what extent did Enlightenment ideals influence the actions that resulted in the storming of the Bastille?

Enlightenment thought played a crucial role. Philosophies emphasizing individual rights, popular sovereignty, and the separation of powers provided an intellectual framework for challenging the legitimacy of the absolute monarchy and advocating for political reform. The members of the Third Estate looked to enlightenment ideals to justify their demands and actions.

Question 3: What was the significance of Jacques Necker’s dismissal in relation to the Bastille event?

Necker, the finance minister, was perceived as sympathetic to the Third Estate and advocated for financial reforms. His dismissal was interpreted as a sign that the monarchy was resistant to change and unwilling to address the grievances of the common people, thus acting as a catalyst for popular unrest.

Question 4: How did economic factors contribute to the conditions preceding the Bastille incident?

Severe economic hardship, exacerbated by poor harvests and rising bread prices, created widespread discontent and desperation among the Third Estate. This economic distress, coupled with an inequitable tax system that disproportionately burdened the poor, fueled resentment towards the monarchy and the privileged classes.

Question 5: Did social inequalities in pre-revolutionary France significantly impact the rise in societal tensions?

The rigid hierarchical structure of French society, characterized by vast disparities in privilege and opportunity, fostered widespread resentment and discontent. The Third Estate, burdened by taxation and lacking political representation, felt marginalized and oppressed by the privileged First and Second Estates.

Question 6: What role did fear play in the events that culminated in the seizing of the Bastille?

Fear was a significant motivator. The fear of royal repression, economic hardship, and starvation drove many Parisians to take drastic action. Rumors of troops amassing in Paris heightened anxieties and fueled the belief that armed resistance was necessary for self-preservation.

The understanding of the incident necessitates consideration of the interwoven influence of economic instability, social inequalities, Enlightenment ideals, political tension, and volatile catalysts that led to revolutionary fervor.

Following this analysis, the article will then review the historical impact of the event.

Conclusion

The preceding analysis elucidates the complex web of interconnected factors that led to storming of Bastille. Fiscal mismanagement, entrenched social inequalities, the galvanizing force of Enlightenment ideals, and the resulting political impasse all coalesced to create a climate ripe for revolutionary action. Popular unrest, fueled by economic hardship and the perceived threat of royal repression, ultimately propelled the citizens of Paris to target the Bastille, a symbol of royal authority.

A thorough understanding of what led to storming of Bastille necessitates a recognition of the multifaceted nature of historical causation. It serves as a reminder of the potential consequences of unchecked power, systemic inequality, and the suppression of legitimate grievances. Further study of these critical precursors to watershed historical events remains essential for informed civic engagement and the pursuit of a more just and equitable future. The study of these historical turning points offers powerful insight on the nature of social structures and political systems which must be applied to build a better tomorrow.

![Bastille Storm's Impact: What Was the Outcome? [Explained] Hubbastille: Explore the Fusion of Culture, Music & Creativity Bastille Storm's Impact: What Was the Outcome? [Explained] | Hubbastille: Explore the Fusion of Culture, Music & Creativity](https://hubbastille.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/th-33-300x200.jpg)