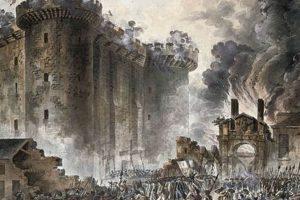

The event on July 14, 1789, represented a pivotal moment in the French Revolution. It was not a singular, spontaneous outburst, but rather the culmination of various interwoven factors creating a volatile atmosphere in Paris and France as a whole. This included social inequalities, economic hardship, and political tensions.

Contributing to the unrest were a number of significant concerns. The French population, especially the Third Estate, faced widespread famine and high bread prices. Resentment towards the aristocracy and the perceived excesses of the monarchy fueled anger. Furthermore, perceived threats from Royal troops exacerbated anxieties. The dismissal of Jacques Necker, a popular finance minister, added to the feeling that reform efforts were being stifled.

This combination of social, economic, and political grievances culminated in the search for weapons and gunpowder. The Bastille, a medieval fortress used as a state prison, represented royal authority and was rumored to hold stores of these essential supplies. The desire to arm themselves against potential royal crackdowns, coupled with the symbolic importance of the prison, led to a confrontation that ignited the French Revolution.

Understanding the Motivations Behind the Attack

Gaining a comprehensive understanding of the events surrounding July 14, 1789, requires examining several contributing factors that converged to motivate the populace.

Tip 1: Analyze the Social Stratification. France’s rigid social hierarchy played a crucial role. Examine the disparities between the privileged First and Second Estates and the burdened Third Estate. Consider how this inequality fostered resentment and a desire for systemic change.

Tip 2: Evaluate the Economic Crisis. Investigate the widespread famine, high bread prices, and overall economic hardship that plagued France in the late 1780s. These conditions fueled popular discontent and desperation, making people more receptive to radical action.

Tip 3: Consider the Political Context. Explore the role of the monarchy, the Estates-General, and the dismissal of Jacques Necker. Understand how perceived royal absolutism and attempts to suppress reform contributed to the escalating tensions.

Tip 4: Recognize the Symbolic Importance. The Bastille was not simply a prison. Its significance as a symbol of royal authority and oppression cannot be overstated. Consider how the attack on the fortress represented a direct challenge to the established power structure.

Tip 5: Investigate the Search for Arms. The populace sought weapons to defend themselves against potential royal crackdowns. Examine the rumors of gunpowder stored within the Bastille and how this motivated the crowds to target the fortress.

Tip 6: Understand the Role of Enlightenment Ideas. The ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity, propagated by Enlightenment thinkers, played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and inspiring revolutionary fervor. Examine how these ideas influenced the actions of the revolutionaries.

By analyzing these factors, a clearer picture emerges of the complex web of motivations that led to the pivotal attack. Understanding these motivations provides critical insight into the start of the French Revolution.

The preceding examination sheds light on the events that marked a turning point in French history. The impact of the fall of the Bastille continues to be felt to this day.

1. Royal Absolutism and the Storming of the Bastille

Royal absolutism, the political doctrine granting the monarch unchecked power, served as a significant catalyst. The perception of Louis XVI’s government as arbitrary and unresponsive fueled widespread resentment. Decisions made without the consent or input of the governed generated deep dissatisfaction, especially within the Third Estate. This system fostered a belief that the King and his court were insulated from the suffering of the common people, exacerbating existing economic and social grievances. Royal decrees concerning taxation and resource allocation disproportionately burdened the lower classes, deepening the chasm between the ruling elite and the populace. The lack of accountability inherent in royal absolutism provided fertile ground for revolutionary sentiment.

The King’s power extended to the arbitrary imprisonment of citizens, often without due process. The Bastille, a state prison, symbolized this aspect of royal authority. Its walls held political prisoners, individuals who had dared to challenge the King’s policies or criticize the regime. The lettre de cachet, a royal warrant allowing for imprisonment without trial, exemplified the unchecked power wielded by the monarchy. These actions instilled fear and distrust in the King’s justice, contributing significantly to the desire to dismantle the existing power structure. The belief that individual liberty was suppressed by royal decree motivated individuals to confront the tangible symbol of absolutist power.

In summary, royal absolutism directly fueled the event on July 14, 1789, because it represented a system of governance characterized by unchecked power, lack of accountability, and suppression of individual liberties. The storming of the Bastille, therefore, was an act of defiance against this oppressive regime, signifying a demand for fundamental political and social change. The dismantling of royal absolutism became a central objective of the French Revolution, underscoring the profound connection between the prevailing political system and the eruption of revolutionary violence.

2. Economic Distress and the Storming of the Bastille

Economic distress served as a significant underlying factor contributing to the social and political upheaval culminating in the events of July 14, 1789. Widespread hardship, coupled with perceived governmental indifference, fueled popular discontent and directly influenced the decision to storm the Bastille.

- Widespread Famine and Food Scarcity

France experienced severe food shortages in the years leading up to 1789, primarily due to poor harvests. Grain scarcity drove up the price of bread, the staple food for the majority of the population. Families faced starvation, and desperation fueled anger towards the government, which was seen as unable or unwilling to address the crisis. The inability to secure basic sustenance served as a direct motivator for the populace to take drastic action.

- High Taxation and Fiscal Burden

The French monarchy’s extravagant spending, coupled with costly involvement in wars such as the American Revolution, led to a severe national debt. To address this debt, the government imposed heavy taxes, disproportionately burdening the Third Estate, which comprised the majority of the population. These taxes further exacerbated the economic hardship faced by ordinary citizens, fostering resentment towards the privileged classes who were largely exempt from taxation. The unfair fiscal system contributed to the perception of injustice and the need for radical change.

- Unemployment and Poverty

Economic policies and trade restrictions led to widespread unemployment, particularly in urban centers like Paris. The influx of rural populations seeking work further strained resources and intensified poverty. The lack of economic opportunity and the growing disparity between the wealthy elite and the impoverished masses created a volatile social environment. This economic deprivation fueled the desperation that prompted participation in revolutionary activities.

- Perceived Governmental Inaction

The perception that the monarchy and the aristocracy were indifferent to the suffering of the common people amplified the impact of economic hardship. The lavish lifestyle of the royal court, contrasted with the widespread poverty and starvation, fueled resentment. The dismissal of Jacques Necker, a finance minister who advocated for economic reforms, further eroded public trust in the government’s ability to address the crisis. This perceived inaction contributed to the sense that only radical action could bring about meaningful change.

The economic conditions in France in the late 1780s created a climate of widespread discontent and desperation. The scarcity of food, the burden of taxation, and the lack of economic opportunity, coupled with perceived governmental indifference, motivated the populace to take drastic action. The storming of the Bastille, while also a symbolic act, was in part driven by the hope of securing resources and challenging a system that had failed to provide for the basic needs of the people.

3. Social Inequality and the Storming of the Bastille

Social inequality in pre-revolutionary France was a fundamental factor that precipitated the storming of the Bastille. The rigid social hierarchy, known as the Estates System, divided French society into three distinct classes: the clergy (First Estate), the nobility (Second Estate), and the commoners (Third Estate). The First and Second Estates enjoyed significant privileges, including exemption from most taxes, exclusive access to high-ranking positions in government and the military, and ownership of vast amounts of land. Conversely, the Third Estate, comprising the vast majority of the population, bore the brunt of taxation, lacked political representation, and faced limited opportunities for social or economic advancement. This stark disparity created deep resentment and a sense of injustice among the commoners, fueling a desire for radical change. The unfair distribution of wealth and power within the social structure directly contributed to the volatile atmosphere that ultimately led to the uprising.

The economic and political consequences of social inequality further exacerbated tensions. The Third Estate, which included peasants, urban workers, and the bourgeoisie, bore the primary responsibility for supporting the state financially. While the privileged classes were largely exempt from taxation, the commoners faced heavy burdens that strained their resources, especially during times of economic hardship and famine. Moreover, the lack of political representation for the Third Estate meant that their grievances were often ignored or dismissed by the ruling elite. The Estates-General, a representative assembly convened in 1789 after a long hiatus, failed to adequately address the demands for reform, leading to further disillusionment and a growing belief that only direct action could bring about meaningful change. The systematic denial of political voice and economic equity reinforced the perception that the existing social order was inherently unjust and unsustainable. For example, the bourgeoisie, though often educated and relatively wealthy, were excluded from holding high office solely based on their social status, further contributing to their dissatisfaction with the established system.

In conclusion, social inequality played a pivotal role in the events on July 14, 1789. The systemic advantages enjoyed by the privileged classes, coupled with the economic and political marginalization of the commoners, created an environment ripe for revolution. The storming of the Bastille was not merely a spontaneous act of violence but a direct response to the perceived injustices of the French social order. The Bastille, as a symbol of royal authority and oppression, became a target for the disaffected masses seeking to dismantle the existing power structure and establish a more equitable society. Understanding the dynamics of social inequality is therefore essential for comprehending the causes and significance of this pivotal moment in French history.

4. Food Shortages and its impact

Food shortages in pre-revolutionary France constituted a critical factor leading to the events of July 14, 1789. A combination of adverse weather conditions, inefficient agricultural practices, and inadequate distribution systems resulted in widespread famine and soaring bread prices, the primary staple for the majority of the population. This scarcity triggered widespread discontent, exacerbating existing social and economic inequalities. The inability of the government to effectively address the crisis fueled popular resentment, contributing directly to the volatile atmosphere that culminated in the assault on the Bastille.

The scarcity of grain and the subsequent rise in bread prices had profound social and political consequences. As food became increasingly unaffordable, urban populations faced starvation and desperation. Riots and unrest became commonplace in Paris and other major cities. For instance, the Rveillon riots, which occurred in April 1789, were sparked by rumors of wage cuts and concerns about rising bread prices. These incidents demonstrated the growing instability and the potential for widespread violence. The perceived indifference of the aristocracy and the monarchy to the plight of the common people further inflamed tensions, leading to a breakdown of trust in the established authorities. Furthermore, in rural areas, peasants faced with food shortages were vulnerable to exploitation by landowners and merchants, contributing to a general sense of grievance and injustice. The storming of the Bastille can be interpreted, in part, as an attempt to secure food supplies and challenge a system that had failed to provide for the basic needs of the population.

In summary, food shortages played a central role in the build-up to the storming of the Bastille. The inability of the French government to ensure adequate food supplies undermined its legitimacy and fueled popular unrest. The combination of scarcity, high prices, and perceived governmental indifference created a climate of desperation and anger that contributed directly to the outbreak of the French Revolution. Understanding the link between food shortages and the Bastille is crucial for comprehending the complex social, economic, and political forces at play during this pivotal moment in European history. The events serve as a stark reminder of the importance of food security and the potential consequences of neglecting the basic needs of a population.

5. Political Tension and its impact

Political tension in pre-revolutionary France served as a crucial and direct precursor to the events of July 14, 1789. The existing political climate, characterized by a disconnect between the ruling monarchy and the governed populace, engendered widespread dissatisfaction and a sense of disenfranchisement. This tension stemmed from perceived royal absolutism, the lack of representation for the Third Estate, and the perceived failure of the Estates-General to address fundamental societal issues. Consequently, the storming of the Bastille can be interpreted as a culmination of these tensions, a direct response to a political system perceived as unresponsive and oppressive. For example, the dismissal of Jacques Necker, a popular finance minister sympathetic to reform, amplified existing anxieties and underscored the monarchy’s resistance to meaningful change. This perceived intransigence heightened political tensions, making conflict more probable.

The power vacuum created by the indecisiveness of Louis XVI and the competing interests within the royal court further destabilized the political landscape. The summoning and subsequent deadlock of the Estates-General demonstrated the inherent limitations of the existing political framework. Representatives of the Third Estate, frustrated by the lack of progress, formed the National Assembly, a direct challenge to royal authority. The King’s initial attempts to suppress this assembly, followed by his reluctant acceptance, created an atmosphere of uncertainty and heightened the sense of crisis. Moreover, rumors of royal troops amassing around Paris fueled popular fears of a crackdown, exacerbating the existing tensions and prompting citizens to seek means of self-defense. The combination of political gridlock, perceived royal threats, and the emergence of alternative political bodies created a highly charged environment where even minor incidents could trigger significant unrest.

In summary, political tension was a central element contributing to the events on July 14, 1789. The perceived failure of the existing political system to address societal grievances, coupled with actions taken by the monarchy that exacerbated rather than alleviated these concerns, created a volatile atmosphere ripe for revolution. The storming of the Bastille represents a direct consequence of this political tension, signifying a rejection of royal authority and a demand for fundamental political change. Understanding the intricate interplay between political tension and the events surrounding the fortress prison is essential for comprehending the origins and the initial spark of the French Revolution.

6. Enlightenment Ideas and the Storming of the Bastille

Enlightenment ideas, with their emphasis on reason, individual rights, and popular sovereignty, provided the intellectual framework that fueled the discontent and revolutionary fervor preceding and during the events of July 14, 1789. These concepts challenged the legitimacy of the existing social and political order, directly influencing the motivations and actions of those who stormed the Bastille.

- Emphasis on Natural Rights

Enlightenment thinkers like John Locke articulated the concept of natural rights, including life, liberty, and property. These ideas resonated deeply with the Third Estate, who felt their rights were systematically violated by the aristocracy and the monarchy. The storming was, in part, an assertion of these natural rights, a rejection of arbitrary rule, and a demand for individual freedom and security. The perceived unjust imprisonment of citizens within the Bastille directly contradicted the Enlightenment’s emphasis on liberty and due process, thereby intensifying the desire to dismantle this symbol of oppression.

- The Concept of Popular Sovereignty

Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s concept of popular sovereignty, which posits that political authority ultimately resides in the people, challenged the divine right of kings. This notion inspired the Third Estate to demand greater political representation and a say in governance. The storming, therefore, can be seen as an act of asserting popular sovereignty, a rejection of the King’s absolute authority, and a demand for a government accountable to the people. The formation of the National Assembly, preceding the attack, exemplified this shift in political thinking, placing power in the hands of the representatives of the nation.

- Advocacy for Equality and Social Justice

Enlightenment thinkers criticized the rigid social hierarchy of the Estates System and advocated for equality before the law and a more just distribution of resources. This critique fueled resentment towards the privileges enjoyed by the First and Second Estates, further motivating the Third Estate to demand systemic change. The dismantling of the Bastille, a symbol of aristocratic privilege and royal oppression, represented a concrete step towards achieving a more egalitarian society, challenging the established power structures that perpetuated social injustice.

- Belief in Reason and Progress

The Enlightenment promoted reason and scientific inquiry as tools for understanding and improving society. This emphasis on rationality encouraged individuals to question traditional authority and seek solutions to social problems through reasoned debate and reform. The storming was, in part, driven by a belief that the existing order was irrational and unjust and that revolutionary action was necessary to bring about progress and create a more enlightened society. The ideas put forth in texts such as Diderot’s Encyclopedia promoted the dissemination of knowledge and critical thinking, ultimately empowering the populace to challenge the status quo.

The influence of Enlightenment ideas on the events of July 14, 1789, underscores the power of intellectual currents to shape social and political movements. The emphasis on individual rights, popular sovereignty, equality, and reason provided a powerful ideological foundation for the French Revolution, directly contributing to the motivations behind the storming and its subsequent impact on French history. These ideas provided a language and justification for challenging the established order, ultimately leading to the dismantling of the Bastille and the pursuit of a more just and equitable society.

7. Symbol of oppression

The Bastille, a medieval fortress repurposed as a state prison, functioned as a potent symbol of royal authority and, critically, oppression. This symbolic weight directly contributed to its targeting during the events of July 14, 1789. The fortress represented the arbitrary power of the monarchy, particularly through the practice of lettres de cachet, royal warrants enabling imprisonment without due process. Its walls held political prisoners, individuals who challenged the King’s authority or expressed dissenting views. The presence of the Bastille in the heart of Paris served as a constant reminder of the government’s capacity to suppress dissent and curtail individual liberties. Thus, it was not simply a prison but a tangible representation of the oppressive system the revolutionaries sought to dismantle.

The importance of the “symbol of oppression” element of the fortress can be best understood by examining the actions and motivations of the revolutionaries. The storming was not primarily driven by a desire to liberate prisoners; in fact, only seven inmates were held within the Bastille at the time. Instead, the target was the symbol itself. The revolutionaries sought to dismantle the Bastille, both physically and metaphorically, as a decisive act against royal absolutism. This act of defiance signaled a direct challenge to the authority of the monarchy and demonstrated the populace’s determination to reclaim their rights and freedoms. Moreover, the capture of the fortress provided access to weapons and gunpowder, crucial resources for further revolutionary actions. However, the symbolic victory held even greater significance, galvanizing support for the revolution and inspiring similar uprisings throughout France. For instance, the destruction of the Bastille was quickly followed by the dismantling of other symbols of feudal power in the countryside, demonstrating the ripple effect of this symbolic act.

Understanding the Bastille as a “symbol of oppression” is vital for comprehending the motivations behind the storming and its subsequent impact on the French Revolution. It was not a mere act of prison liberation or a simple quest for arms. Instead, it was a calculated assault on the visible manifestation of royal authority and a resounding declaration of the people’s will to overthrow an oppressive regime. Recognizing this symbolism allows one to appreciate the far-reaching consequences of the event, not only as a pivotal moment in French history but also as a powerful demonstration of the potential for popular resistance against tyranny. While challenging, effectively addressing deeply ingrained symbolic representation demands commitment to structural and systemic change.

Frequently Asked Questions

The following section addresses common inquiries and misconceptions regarding the convergence of factors that led to the events of July 14, 1789.

Question 1: Was the primary motivation the liberation of prisoners held within the Bastille?

While the Bastille served as a prison, the liberation of its inmates was not the primary driver. The fortress held only a handful of prisoners at the time. The storming was primarily motivated by the desire to acquire weapons and gunpowder, and more importantly, to strike a symbolic blow against royal authority.

Question 2: To what extent did economic factors influence the storming of the Bastille?

Economic distress played a crucial role. Widespread famine, soaring bread prices, and high unemployment created widespread discontent and desperation among the Third Estate, making them more receptive to revolutionary action.

Question 3: How did Enlightenment ideals contribute to the storming of the Bastille?

Enlightenment principles, emphasizing natural rights, popular sovereignty, and social justice, provided the intellectual justification for challenging the existing social and political order. These ideas inspired the Third Estate to demand greater political representation and a more equitable society.

Question 4: What was the significance of royal absolutism in the events leading up to July 14, 1789?

Royal absolutism, characterized by the monarch’s unchecked power and lack of accountability, fueled resentment and a sense of disenfranchisement among the populace. The perception of arbitrary rule and the suppression of individual liberties contributed directly to the desire for radical change.

Question 5: Did the social structure of pre-revolutionary France play a role in the storming of the Bastille?

The rigid social hierarchy of the Estates System, with its inherent inequalities and privileges, created deep divisions within French society. The Third Estate, burdened by taxation and lacking political representation, sought to dismantle the system that perpetuated its marginalization.

Question 6: What role did food shortages play in the events leading to the Bastille?

Severe food shortages and soaring bread prices directly increased social tensions. As the state was unable to ensure basic food availability, the authority was quickly lost.

In summary, the storming of the Bastille was the result of a complex interplay of political, economic, social, and intellectual factors. It marked a pivotal moment in the French Revolution, symbolizing a rejection of royal absolutism and a demand for fundamental change.

The following section will explore the immediate and long-term consequences of the storming of the Bastille, and its significance for France and Europe as a whole.

Conclusion

This exploration addressed why did the storming of bastille happen, highlighting key factors contributing to the event. These included royal absolutism, economic distress, social inequalities within the Estates System, food shortages, the influence of Enlightenment ideals, and the Bastille’s symbolic representation of oppression. These elements converged to create an environment ripe for revolutionary action.

Understanding the convergence of social, economic, and political grievances leading to the attack allows a deeper appreciation of the event’s enduring significance. Its legacy persists, reminding subsequent generations of the potential consequences of unchecked power, systemic inequality, and the denial of fundamental human rights. Studying this event provides a crucial lens for evaluating contemporary challenges and advocating for just and equitable societies.

![Bastille Storm's Impact: What Was the Outcome? [Explained] Hubbastille: Explore the Fusion of Culture, Music & Creativity Bastille Storm's Impact: What Was the Outcome? [Explained] | Hubbastille: Explore the Fusion of Culture, Music & Creativity](https://hubbastille.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/th-33-300x200.jpg)